A new species of prehistoric croc that prowled the waterways of south-eastern Queensland millions of years ago has been unveiled by University of Queensland researchers.

PhD candidate Jorgo Ristevski, from UQ’s School of Biological Sciences, led the team that named the species Gunggamarandu maunala after analysing a partial skull unearthed in the Darling Downs

“Gunggamarandu belongs to a group of crocodylians called tomistomines or ‘false gharials’,” said Jorgo Ristevski.

“Today, there is only one living species of tomistomine, Tomistoma schlegelii, which is restricted to the Malay Peninsula and parts of Indonesia.”

“With the exception of Antarctica, Australia was the only other continent without fossil evidence of tomistomines. But with the discovery of Gunggamarandu we can add Australia to the ‘once inhabited by tomistomines’ list.”

Since the end of the Age of Dinosaurs 66 million years ago, Australia has been inhabited by numerous species of crocodylians, most of which are extinct. The vast majority of these extinct crocs belong to the group called Mekosuchinae.

“For the better part three decades, the consensus has been that the Australian fossil croc fauna was dominated by mekosuchines. The two species of Crocodylus that inhabit Australia today, the Indo-Pacific crocodile and the Australian freshwater crocodile, are not mekosuchines, and they only first appear in our fossil record a few million years ago.”

“With the exception Antarctica, other continents have been inhabited by multiple croc lineages at some point in the past 66 million years,”

“The discovery of Gunggamarandu maunala demonstrates that the croc diversity in Australia was greater than previously thought, and not as different from the rest of world as once assumed.”

“The fossil skull was discovered somewhere on the Darling Downs region of south-eastern Queensland, and therefore, represents the southern-most record of a tomistomine in the world,” Ristevski said.

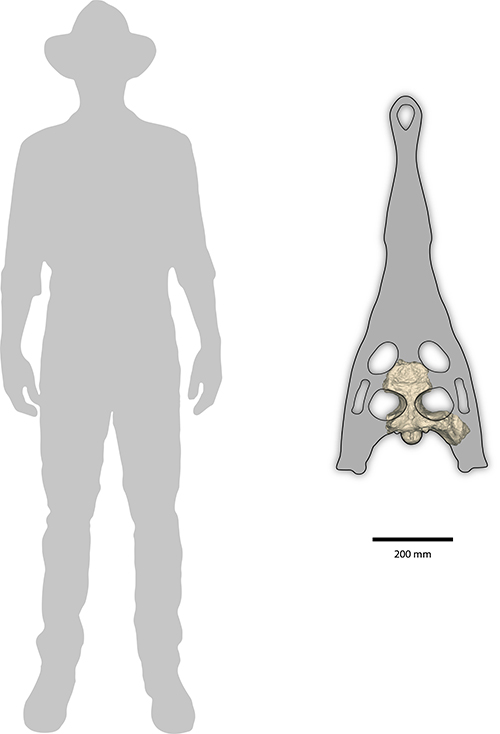

“At the moment, it is difficult to estimate the overall size of Gunggamarandu maunala since all we have is the back of the skull. But it was big.”

“We estimate the skull would have been at least 80 cm long. Based on comparisons with living crocs, this indicates a total body length of around 7 m (23 feet). This suggests Gunggamarandu maunala was on par with the largest Indo-Pacific crocs (Crocodylus porosus) recorded.”

“It is one of the largest crocs to have ever inhabited Australia,” Ristevski said.

“We also had the skull CT-scanned, and from that we were able to digitally reconstruct the brain cavity which helped us in unraveling details of the anatomy that are otherwise impossible to observe.”

“The exact age of the fossil is uncertain, but it is probably between 5 and 2 million years old,” Ristevski said.

Gunggamarandu maunala would have lived alongside giant browsing marsupials like species of Euryzygoma, and a marsupial lion, Thylacoleo. It may have shared the waterways with another large crocodylian, the mekosuchine Paludirex vincenti.

“Gunggamarandu is most closely related to tomistomines that lived in Europe some 50 million years ago. This finding implies that the origins of Gunggamarandu are European. Tomistomines probably arrived in Australia via southeast Asia,” Ristevski said.

Since its initial discovery, the fossil skull of Gunggamarandu maunala remained a scientific mystery for well over a century.

The specimen piqued the interest of Dr Steve Salisbury back in the 90s when he was a young graduate student, but a formal study was not done until Jorgo examined it as part of his PhD thesis.

“I knew it was unusual and potentially very significant, but I never had the time to study it any detail,” Dr Salisbury said.

The name of the new species honours the First Nations peoples of the Darling Downs area where the fossil was found. It incorporates words from the languages of the Barunggam and Waka Waka nations.

“The genus name, Gunggamarandu, means ‘river boss’, whereas the species name, maunala, means ‘hole head’. The latter is in reference to the large, hole-like openings located on top of the animal’s skull that served as a place for muscle attachment.” Salisbury said.

The research has been published in the open access journal Nature Scientific Reports.

Read the UQ News media release here

Media: Mr Jorgo Ristevski, j.ristevski@uq.net.au, +61 422 219 697; Dr Steve Salisbury, s.salisbury@uq.edu.au, +61 407 788 660